Meet Mary, an accomplished photographer specializing in documentary and portrait photography – and shortlisted for the 2023 Student Photographer of the Year for the Sony World Photography Awards.

As a person of Nigerian heritage and a devout Christian, Mary’s work always bears a piece of her identity, diversity, and faith. Having dedicated six years to honing her craft, Mary understands the importance of discovering one’s purpose and embracing personal passions – and bringing those to life via her imagery and stories.

We had a chat with Mary about how she turned an essential part of herself into an impressive shortlist submission for the SONY World Photography Awards and her experiences in the medium.

You’ve recently been shortlisted for the SONY World Photography Awards with your project “Expressions of Worship.” What was your brief?

The series was created in response to Sony’s brief, ‘In a Changing World,’ which asked for positive stories motivated by topics such as the environment, technology, and how we work and live. We were told to create work for this as part of a module brief and asked to interpret it mindfully but creatively. When coming up with an idea, I had to consider how I would respond to all kinds of situations, particularly those from the last few years, both good and bad.

How did being in the spotlight at one of photography’s most influential events feel?

I’m still surprised by the whole thing as I had no expectations after completing my work. I was pleased to have produced something that honestly represents myself and is as essential to me as it is to others. I am thankful for the experience, and others may resonate as well. I was very nervous and did not expect love, encouragement, or criticism.

Getting back to your project, can you tell us more about its idea? What motivated it?

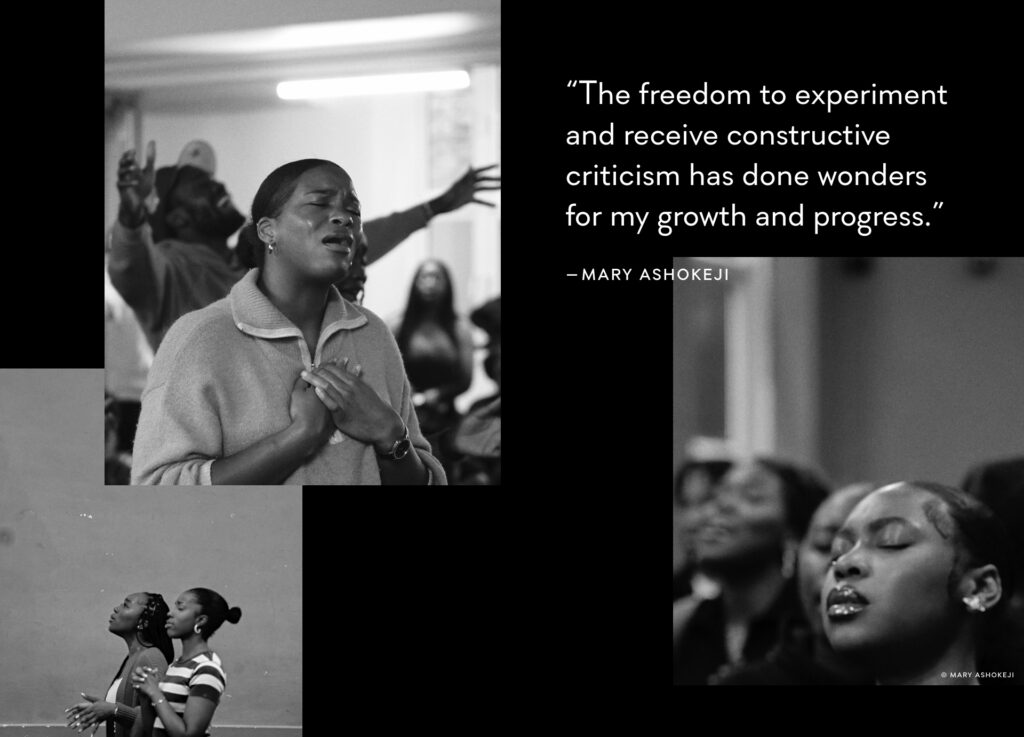

I usually shoot for my church’s social media and see how I could use this. My friend runs a ministry called ‘Expressions of Worship,’ and I started shooting for it, where the name and idea originated. This was a wonderful visual representation of ‘the triumph over adversity.’ Because I am a Christian, I spend much time in prayer, communing with God, even when I doubted my faith and beliefs. Worshipping under challenging circumstances is where I find peace, joy, and solace. Worship is a way of self-expression that presents itself in several ways.

Your photography captures emotions in a very unfiltered way. How did you develop this approach?

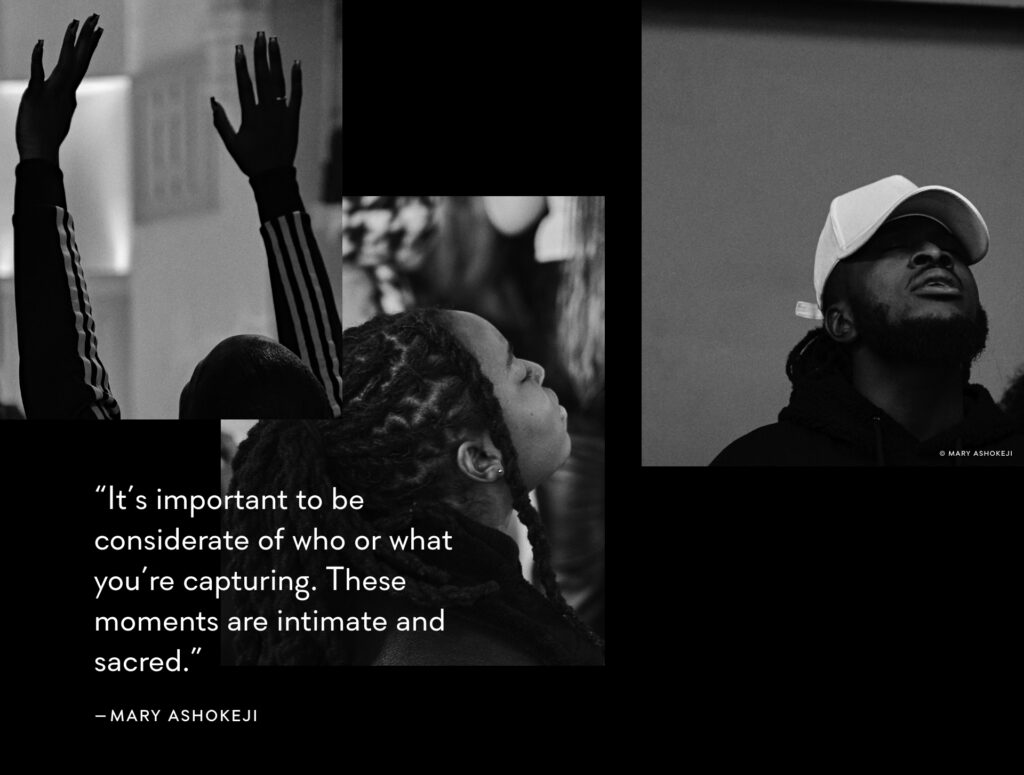

I want to think this is because of how passionate the people are and because of the environment. I usually take the lead during praise and worship at church, and I wanted the experience to feel real for the viewer. The atmosphere is amazing and so immersive. I love negative space and rules because they draw you in and enhance the main focus of the picture. I used a lot of cropping and chose black and white to limit distractions.

How do you work with subjects when capturing such intimate moments?

It’s important to be considerate of who or what you’re capturing. These moments are intimate and sacred. They mean much more to those in them than you. You are ‘just’ capturing it for art or work. I was grateful that my church and the body allowed me to do this.

On a different note, how has studying at Ravensbourne University helped you become a better photographer?

I am immensely grateful to the tutors on my course because they have pushed me to explore exciting opportunities, such as Sony and the publishing industry. Ravensbourne offers a great learning environment that encourages trial and error, where I can learn from the talented individuals around me. The freedom to experiment and receive constructive criticism has done wonders for my growth and progress. Ravensbourne’s SEEDS program has been a fantastic source of my professional and personal development. It helped widen my perspective by showing everything possible in freelancing, networking, self-confidence, and entrepreneurship. One of the greatest benefits of this program was the opportunity to work with a mentor of my choice and all-time favorite photographer. Their advice and insight have had a big impact on my journey.

Follow along with Mary as she edits one of her photos to bring out the detail of the scene.

Back to your roots, what was your first experience in photography? How did you get into it?

I was a big fan of film and cinematography. I would take stills or screenshots of films with great grading and even study color theory. I’ve always struggled with education because I wasn’t aware I had ADHD. Still, after my GCSEs, I discovered a passion for art and photography. My first experience with photography came in A-levels, where I studied fine art photography and media. I didn’t do great at A level, and I didn’t receive an ADHD diagnosis until 20. Before this, I attended college for a BTEC in art design and photography. I had the opportunity to expand my knowledge and skills in photography, studio work, and film, all while gaining a better understanding of the subject.

What were some of the biggest challenges you’ve faced in your young career, and how did you overcome them? Any advice for other upcoming photographers?

I struggled with self-doubt and imposter syndrome. I think it’s vital to acknowledge your feelings and see precisely where they are coming from, whether it’s a comparison or doubt in your abilities and what you think you’re capable of. I think it’s crucial to remember how much you love what you do and why you are doing it. You’re doing your work for yourself. The sooner you stop comparing yourself, the better.

On a different note, when did you first come across Capture One? What role does the software play in your workflow?

I started using Capture One at Ravensbourne, and it’s impressive in functionality. Been a game-changer for me in post-production and allows me to explore and experiment with my images. It opened a world of things that I didn’t know before. I particularly like creating my own presets, allowing me to develop a unique style and aesthetic in multiple images with less going over. The software’s export and import features have also been handy, making handling multiple files and organizing them into groups using the color tab and ratings effortless.

Finally, are you working on any exciting projects you want to tell us about?

I have an extended version of the ‘Expressions of Worship’ series with 50+ images that will be published as a book. A close friend of mine, Esther-Renee Walker, a writer, poet, and actress, has also provided musings on worship. I wrote my dissertation on young black boys and if preconceptions and society have stopped them from exploring themselves and finding their passions. Whether they have been able to follow what they’re passionate about or even find out what you’re passionate about. I have pictured young black men from different walks of life for a photo book on this and have interviewed them on their current careers, childhood, and their aspirations.

See more of Mary’s work on her Instagram and website.

Are you a student? Register here and get a 65% discount on Capture One Pro